Financial System

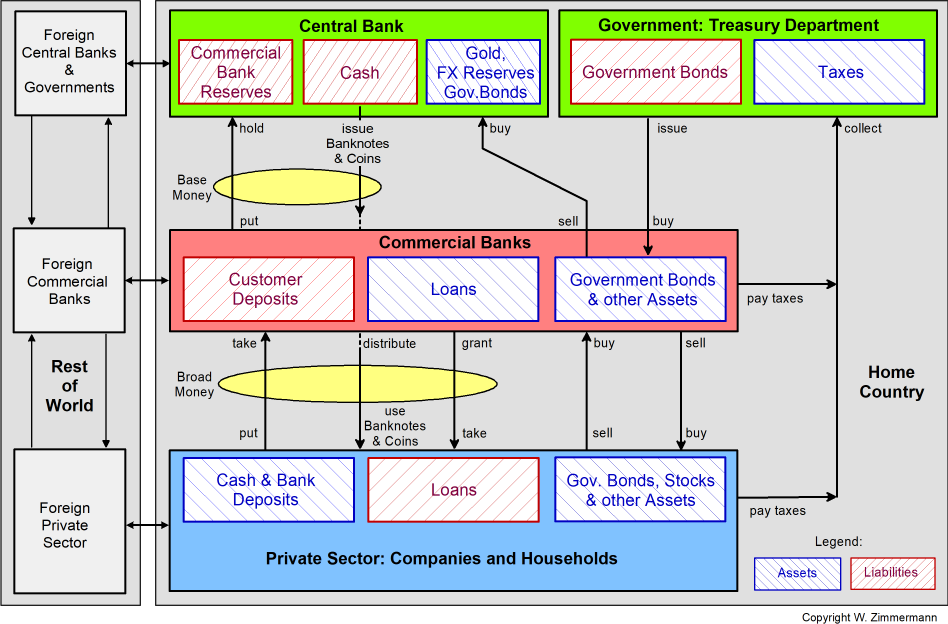

The financial system (Ref. 2 and 4) of a country has a layered structure (Fig. 1):

- At the top of the structure is the central bank (FED, ECB, ...), which issues the country's official cash (banknotes and coins) and implements its monetary policy to ensure the stability of the country's currency. In theory, the central bank is independent. But in most countries, their heads and boards of directors are appointed by the government and thus act in close cooperation with the Treasury Department (Ministry of Finance, Finanzministerium) and their fiscal policy. Central banks hold assets such as gold and government bonds to back the financial system. The central bank's foreign exchange (FX) reserves are usually held in the form of foreign government bonds.

- Below the central bank are the commercial banks that interact directly with the private sector. These commercial banks hold the deposits of the companies and households of the private sector and at the same time must have a defined amount of reserves in accounts at the central bank. Financial transactions between banks are often executed simply by transfers between their accounts at the central bank. In addition to the reserves at the central bank, commercial banks often hold assets like bonds or equities to back up their liabilities and earn money by trading them.

- Private households and companies use small amounts of cash for everyday payments, but the majority of their "money" is in their deposit accounts at commercial banks. If they need more money than they have, they can apply for a loan from a commercial bank. The loan will be granted if the bank believes that the applicant is able to repay the loan and the associated interest, which for most banks is their primary income. For the private sector, both their own deposits and the loans they receive are money they can spend or invest (Ref. 1).

- The government collects taxes from the private sector and from the commercial banks. If they do not get enough money to fulfill all the promises of their politicians, they issue government bonds. These government bonds are sold to commercial banks and they resell them to the private sector (or to the central bank).

In today's globalized world, every level of a country's financial system has partners in other countries. Central banks collaborate, particularly during times of crisis. Large commercial banks have international branches that help companies finance their international operations. Private households purchase goods from online stores in other countries, book hotels, and rent cars, thereby creating their own streams of exports and imports.

Fig. 1 does not show two factors that may have a growing influence on the financial system in the future:

- Shadow banks such as some private equity firms or hedge funds may operate in the credit market, but outside of the regulatory framework and oversight that commercial banks must follow.

- Digital cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin try to establish a global monetary system which is independent of governments and central banks. Governments have started to regulate and tax the crypto world with the argument of protecting users from fraud, and not at least to avoid losing control. And central banks are working on their own version of digital currencies, which anyone could hold directly in a wallet at the central bank. You may not need a bank account at all if you run your own wallet on your private computer or other hardware. This would allow bypassing or eliminating the commercial banks for most, if not all, transactions.

Money Out of thin Air

The commercial banks hold part of their "money" in accounts at the central bank for operational purposes. In most countries the central bank and government regulations define a minimum value for these reserves to ensure liquidity of the commercial banks, but they do not set a direct limit on the total size of the loans the commercial banks can issue. In normal times, the commercial banks will grant far more loans than they have in reserves at the central bank or deposits from their customers. Like the deposits, these loans are nothing more than numbers in the bank's computer system. Thus granting loans is called creating money out of thin air.

To describe and quantify this system, economists use some technical terms:

- The sum of cash and the required reserves of the commercial banks is called base money M0. Its size is regulated by the central bank.

- The sum of all public sector deposits and loans granted by commercial banks plus the cash in circulation is called broad money M2 (sometimes also M3, definitions vary across central banks).

- In 2025 base money M0 in the U.S. was in the range of $5 trillion, whereas broad money M2 was about $22 trillion, that is, the ratio M2 to M0 was a bit more than 4 (see Ref. 3 for current data). The historic name for this ratio is money multiplier. Another historic term is fractional reserve, because the commercial banks' reserves at the central bank are only a fraction of their liabilities.

Broad money, that is, credit created money, is what fuels the economy. The more money flows the better for the economy, as one person's spending is another person's income (Ref. 1). The total credit volume depends on the interaction of the commercial banks with the private sector, that is the willingness and ability to take and grant loans. If companies see business opportunities that promise higher returns than the interest on their loans, they will take out new loans. If the banks believe, that the debtors are able to repay the loans plus interest cost, and if the interest revenue is higher than the banks own costs, they will grant the loans. Thus, capital-market interest rates, which ultimately depend on the key interest rate set by the central bank, play a decisive role in credit creation. The total credit volume is limited by the capital that is available to the banks:

- The most important risk control mechanism limiting credit creation are capital requirements (e.g. Basel III CET ratio). To absorb possible losses, a bank's capital must always be above a certain percentage (8 ...10%) of its assets. (Remember: Loans issued by the bank or government bonds held by the bank count as assets of the bank. But if the customer does not repay or if the government bonds decline because of high inflation rates, the loans or bonds actually become a risk which depletes the bank's capital.) To meet capital requirements, the bank must raise fresh capital, e.g. by issuing new shares, or reduce risk assets, i.e. credit creation.

- A commercial bank must always have enough reserves in its central bank account for its day to day operations. For example, if company A pays a large sum to company B, which uses another commercial bank, the transfer is executed between the two commercial banks' accounts at the central bank. Or if a bank's customers take out a large amount of cash, the commercial bank receives the cash from the central bank, which in turn debits the bank's central bank account. To reduce the operational risk, most countries force their commercial banks to have a certain amount of liquid reserves relative to customer deposits and expected outflows (e.g. Basel III Liquidity Coverage Ratio).

One Man's Debt is Another Man's Asset

When looking at Fig. 1 from a bookkeeping perspective that requires assets and liabilities to be balanced, it is easy to see that we live in a fiat currency system where money actually is sort of a circular credit scheme:

- From the private sector's perspective their bank deposits and the bonds they hold are assets, their loans are liabilities.

- For the commercial banks, the same deposits are liabilities, while the same loans and their reserves at the central bank are assets.

- For the central bank these reserves and the cash in circulation are liabilities. To a small extent, the central bank backs them with gold, which is a hard asset without a counterparty. The rest is implicitly backed by the government.

- Government bonds, whether owned by the central bank, commercial banks or the private sector, are liabilities of the government, which the government "backs" by the capability of the private sector to pay taxes. So the circle is closed.

As is easy to see, one man's debt is another man's asset:

- If a company or household defaults on a loan, the issuing commercial bank loses money. This for example happened in the Great Financial Crisis GFC, when many U.S. households defaulted on their home mortgages. Many commercial banks and private sector entities which held these mortgages directly or indirectly via mortgage backed securities MBS or similar financial instruments lost money.

- If a government defaults on its debt, everybody who holds their government bonds loses money. And because the creditworthiness of the country will suffer, the country's taxpayers will suffer too in the following austerity period. This is what happened when Greece went broke in the Euro crisis in the early 2010s.

Monetary and Fiscal Policy

The primary monetary policy instruments for the central banks to ensure the stability of the financial system are the required size of commercial bank reserves and the key interest rate (Fed Funds Rate, Leitzins), which the central bank pays to the commercial banks for these reserves:

- When the central bank wants to reduce consumer price inflation CPI, it increases this key interest rate. All other interest rates in the country, that is, the price of money, are based on the central bank's rate and thus will also rise. This makes keeping money in bank accounts to earn interest more attractive, while taking loans becomes less attractive. In effect, all else equal, less money will be spent by the private sector, economic activity, and thus prices and the inflation rate, should slow down.

- If the central bank increases the required reserves that commercial banks must keep in their central bank account, their liquidity decreases and will create a similar effect.

- The opposite occurs when the central bank decreases the central bank interest rate. Money becomes cheaper, more loans will be granted and this should stimulate the economy, stop deflationary effects and unemployment.

- When banks or insurance companies run into liquidity problems and do not get short-term credit from other banks in the interbank market, the central bank may execute a repo (repurchase) operation, where it buys government bonds from the bank and agrees to sell them back at a future date and slightly higher price. Repo and reverse repo operations are often used by central banks for short-term management of interest rates.

Governments care less about inflation in their fiscal policy, but more about consumer, aka voter, sentiment. Their main instruments are taxes and government spending:

- When the economy is booming, tax revenue allows them to pursue their political goals and spend money for their pet projects. They may increase or decrease taxes to force certain developments such as the renewable energy transition. This is why governments love moderately inflationary environments. As a nice side effect, inflation reduces the real value of existing government debt and the inflationary growing GDP reduces the debt to GDP ratio.

- When the economy struggles and unemployment soars, that is, when the environment is deflationary, they fear losing voters and their mandate in the next election. So they try to stimulate the economy by relaxing regulations and promising tax cuts. Despite lower tax revenue, in extreme situations such as the GFC or the Covid-19 crisis, they may even hand out additional money to support fired workers, provide subsidies for industries under pressure or directly send checks to households to increase their purchasing power.

Economists prefer monetary dominance, where central banks can set interest rates freely to control inflation and currency exchange rates. However, when governments accumulate large deficits, central banks may be forced to keep interest rates low and even monetize the debt. This is called fiscal dominance, for more details see this post.

Currency Exchange Rate Management

Currency exchange (FX) rates indicate the real or perceived relative strength of an economy, at least in theory. In the real world, FX rates depend on supply and demand dynamics and react volatile to changes in a lot of economic variables:

- A country which has a real higher interest rate (real rate = nominal interest rate minus inflation rate) or a more attractive financial market than its peers should see capital inflows and thus its currency should become more expensive.

- A country with a trade surplus sees earnings from exports flow into its economy and thus its currency should become more expensive.

- In a geopolitical crisis people often sell foreign investments and repatriate their capital into their home country or another perceived safe-haven country. In the past such countries were the U.S., Japan or Switzerland.

- If a country prints more money, its currency should become cheaper, as the value of the country's hard assets such as its industry, natural resources and real estate does not change, but is now represented by more currency units.

Export-oriented companies often prefer a weaker home currency, because it makes their exports look cheaper for foreign buyers of their products. Private households however tend to prefer a stronger home currency, as it makes imported goods and services or traveling to foreign countries cheaper.

Because FX rates influence local inflation and deflation, most central banks manage their currency exchange rate, even if few will openly admit it:

- A central bank can buy foreign currencies or foreign assets such as stocks or bonds and pay with their home currency. This can be used to make the local currency cheaper to help the export-oriented industry or shield the local industry against cheap imports. Theoretically there is no limit for this strategy, as the central bank pays with its own currency, which it can print as required. The Trump administration, for example, blames China and the EU for using this strategy to maintain their trade surplus. Switzerland used to buy a lot of international stocks to stop the strongly appreciating Swiss franc in the Euro Crisis.

- A central bank can sell FX reserves or gold and buy its own currency to make the currency stronger. This is typically used to stabilize a depreciating home currency and stop import-induced inflation. As the central bank cannot print foreign currencies, this is limited by the amount of reserves which have been acquired before.

- If a central bank cannot stabilize its currency or if a government has other concerns about capital flowing into or out of a country, they can implement outright capital controls. For example, some countries implement limits on how much money may be transferred across the border and many countries forbid or restrict real estate or local companies purchases by foreigners.

Eurodollar Market

Because international trade is often settled in U.S. dollars, non-U.S. commercial banks in many countries allow their customers to hold deposits or loans in U.S. dollars (or other currencies) instead of their home currency. Companies often take credit in dollars to finance their international activities and households in countries with high inflation and weak currencies tend to hold savings in dollars. This so-called Eurodollar market, despite its name, is not restricted to Europe but extends to the Middle East and Asia. The Bank for International Settlements BIS estimates the amount of offshore dollars to be in the same range as the broad money supply inside the U.S. While the Eurodollar market functions well in normal times, the Fed and the U.S. Treasury cannot control its size and regulate it. In a crisis situation like the GFC or the Covid crisis the market can dry up and the non-U.S. banks and companies may have problems servicing their U.S. dollar liabilities. In such a scenario, their local central bank is expected to step in as lender of last resort, if necessary with printed money. But a non-U.S. central bank cannot print dollars, so it may not be able to help. In past risk situations, the U.S. central bank Fed used to install emergency swap lines with the non-U.S. central banks, e.g. the ECB. Swap lines are essentially time-limited credit agreements between central banks, so that the non-U.S. central banks can forward dollars to their local commercial banks.

Related Posts:

References:

- Ray Dalio: How the economic machine works, 2019

- Lyn Alden: Broken Money, 2023

- Tradingeconomics.com: United States Money Supply

- Cullen Roche: Understanding the Modern Monetary System, 2011-2023

- Bundesbank (German Central Bank): The role of banks, non-banks and the

central bank in the money creation process, 2017 - Bank of England: Money creation in the modern economy, 2014